Human pancreatic cancer model offers new opportunities for testing drugs

╣·▓·¥½ãÀ scientists have grown human pancreatic cancer tumours in the lab ÔÇô their model is the first of its kind, with important future clinical implications.

╣·▓·¥½ãÀ scientists have grown human pancreatic cancer tumours in the lab ÔÇô their model is the first of its kind, with important future clinical implications.

Isabelle Dubach

Media and Content Manager

+61 432 307 244

i.dubach@unsw.edu.au

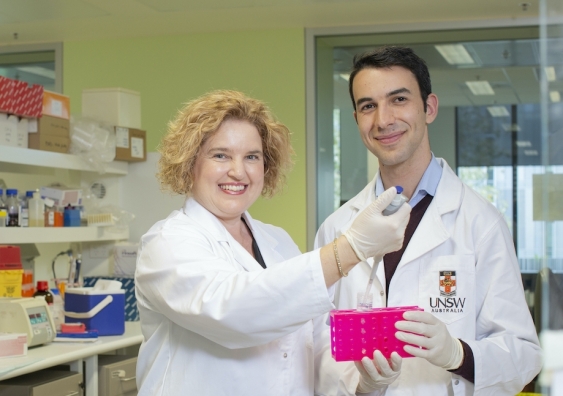

A team of medical researchers at ╣·▓·¥½ãÀ have achieved a unique milestone in the fight against pancreatic cancer: led by world-leading cancer biologist Associate Professor Phoebe Phillips, the multi-disciplinary team has successfully grown a complete human tumour model in a petri dish.

Crucially, the teamÔÇÖs model stays intact for 12 days and offers a complete view of the tumour ÔÇô an approach that has great potential for testing the effect of different drugs on the cancer, and offering personalised medicine approaches to patients down the track.

The findings are published today in .

╣·▓·¥½ãÀ Scientia PhD student John Kokkinos, who was set the challenge to create such a model by A/Prof. Phillips at the outset of his PhD, says current tumour models are limited. John was grateful to receive a scholarship to complete this project.

ÔÇ£One of the current gold standard models for testing therapeutics is the mouse ÔÇô you give them pancreatic cancer and then test different treatments, but mouse tumours do not perfectly mimic the biology of the disease in patients,ÔÇØ Kokkinos says.

ÔÇ£Our ambitious vision ÔÇô and the project IÔÇÖve been focused on for three years ÔÇô was to take a human pancreatic tumour and keep it alive in a dish. If we could do that, we could use it to test which chemotherapeutics a patientÔÇÖs tumour may respond best to.ÔÇØ

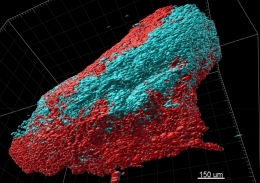

The multi-disciplinary team has successfully grown a complete human tumour model in a petri dish. Image: Scientific Reports,

The unique advantage of the teamÔÇÖs approach is the fact that they didnÔÇÖt just grow the tumour cells, but the tumourÔÇÖs surrounding area, too. That makes it very different from the usual scientific approach of using so-called organoids.

ÔÇ£One of the hottest topics in cancer research is organoids, which basically involves taking tumour cells from a patient, isolating them, and then allowing them to form little 3D tumour masses,ÔÇØ Kokkinos says.

ÔÇ£And so you're left with just the tumour cells, and you've got no other surrounding cells, such as immune cells, scar tissue, blood vessels ÔÇô which are all really critical in promoting the aggressiveness of the tumour.

ÔÇ£Think of these surrounding cells as the fortress that promotes tumour growth ÔÇô it can really be a key player in driving resistance to chemotherapy.

ÔÇ£ThatÔÇÖs why we felt that looking at tumour cells by themselves doesn't really represent the true clinical picture.ÔÇØ

To keep everything intact, the team took the surgical piece of pancreatic tumour and developed a way to keep it alive for 12 days in an incubator in the laboratory.

ÔÇ£So essentially, we are trying to mimic the tumour in a way that best allows us to test therapeutics,ÔÇØ A/Prof. Phillips says.

ÔÇ£This is the first model of its kind that lasts this long ÔÇô other labs have done something similar, but only for two or three days, and even then it doesn't quite maintain the viability and the architecture of the tumours.

ÔÇ£We also characterised the tumourÔÇÖs different cell types over time, and were able to show that these cell types don't change. They maintain all of their characteristics in that 12-day period.ÔÇØ

While the team would love to be able to keep the tumour alive even longer, 12 days seems to be the current maximum.

ÔÇ£When we get the tumours from the patient, they are grown on a scaffold ÔÇô that scaffold starts to degrade, and so we're stuck with that time point,ÔÇØ A/Prof. Phillips says.

ÔÇ£But we want to work with our engineering colleagues to modify that scaffold to increase its life.ÔÇØ

The end goal of developing such a model is to be able to test the effect of different drugs ÔÇô both broadly and in terms of how they work on individual patientsÔÇÖ tumours.

ÔÇ£What it will allow us to do is test up to 10 different drugs simultaneously on a surgical specimen,ÔÇØ Kokkinos says.

ÔÇ£Because you get the result in a couple of weeks, you could go back and inform the clinical team about which drug is working best on a particular patientÔÇÖs tumour ÔÇô we hope that itÔÇÖll end up being a really rapid way to feed back into the clinical situation.ÔÇØ

Reflecting on the journey that got the team to this milestone, Kokkinos says itÔÇÖs been a process of trial and error.

ÔÇ£It was a bit of a risk to start off with, I must say ÔÇô we didn't really know how it was going to turn out. There were a lot of failures along the way, things weren't working out, but we kept persevering: we tried different things, we constantly went back to the drawing board.ÔÇØ

He remembers the first time he realised their idea might just work. ÔÇ£I must say the first time we actually got it right and we saw that the tumour architecture and the viability was maintained for 12 days, that was something quite extraordinary.

ÔÇ£And then from there, it was about characterising the model, and looking at the individual cells that make up these mini tumours that we were growing, and then starting to test both the clinical drugs and the novel drugs, including our nanomedicine.ÔÇØ

In todayÔÇÖs publication, the team describe in detail how their model works, and theyÔÇÖve tested reproducibility across a couple of dozen patients. Now, they need funding to gather more data before this could be used as a clinical tool.

ÔÇ£Now, we want to actually show that our model does predict patient response accurately. That's the next stage for us,ÔÇØ A/Prof. Phillips says.

The team also want to address one of their modelÔÇÖs biggest limitations: so far, theyÔÇÖve exclusively worked on tumours from patients that had surgery.

ÔÇ£That represents about 15 to 20 per cent of patients with pancreatic cancer, as the vast majority of patients don't have a tumour that's surgically resectable. So what we really want to try and do is be able to obtain tumour samples from patients that have metastatic disease, so that we can include all of the patients that have pancreatic cancer,ÔÇØ Mr Kokkinos says.

ÔÇ£So we're looking into ways to do that ÔÇô we are collaborating with clinicians and gastroenterologists to be able to take samples from a biopsy, and hopefully be able to use the model for those patients as well.ÔÇØ

The team say their model has the potential to be used globally.

ÔÇ£We think that this is a relatively simple model that can be adapted by multiple labs around the world,ÔÇØ Kokkinos says.

ÔÇ£They can take this model and use it on developing their own drugs. WeÔÇÖre also hoping this will enable us to establish new collaborations with other leading researchers.ÔÇØ

Pancreatic cancer has a five-year survival rate of only 10.7 per cent, and is expected to become AustraliaÔÇÖs second leading cause of cancer mortality by 2025 ÔÇô which is why itÔÇÖs high on the agenda of health authorities in Australia, too: for example, is part of an advisory committee working on AustraliaÔÇÖs to support improved outcomes and survival for people with pancreatic cancer, which Cancer Australia and the Department of Health are leading. She is also the co-lead of ╣·▓·¥½ãÀÔÇÖs , AustraliaÔÇÖs first ever centre dedicated to preventing, treating, and eventually curing a cancer.